The Billion Dollar Cavern

SME | Published on June 25, 2024

It might sound strange that a bustling industrial park responsible for thousands of jobs and billions of dollars could have its fate tied to a limestone cavern the size of a studio apartment. When projects take an unexpected turn – like a sprawling cave affecting building placement in a public works project – getting schedules and budgets back on track can seem impossible. Fortunately, SME specializes in unique challenges, and we were more than up to the task when warm air came streaming from gaps in the earth on the River Ridge Commerce Center WWTP Expansion site one icy February morning.

In southern Indiana, the River Ridge Commerce Center employs more than 18,200 workers across the technology, science, and transportation industries and generates over $1.2 billion of business annually. While the commerce center has boomed, the increased economic activity created more stress on the local wastewater treatment plant in Jeffersonville, Indiana. Jeffersonville and the River Ridge Development Authority agreed in late 2022 on a joint $14 million project to double the facility’s treatment capacity, accommodating the commerce center’s growth.

Construction was going steadily when a problem emerged on the site intended for an oxidation ditch. SME’s long-standing partner, the Lochmueller Group, noticed warm vapor rising from fissures in the ground. Lochmueller asked SME’s Wes Hemp, PE, PG, LEED AP of our Louisville Metro office to conduct a geotechnical evaluation.

“Once they mentioned that steam was rising from the fissures, I knew I had to get to the site,” says Wes. “It indicates an underground feature, like a cave, because the air inside stays warm all year. But I didn’t know what to expect because caves are rare; I’ve only encountered two or three in my career.”

At that point, the team had discovered a four-foot-wide limestone shaft going down about nine feet to a stone ledge at the bottom. The infrastructure upgrade critical to the region’s economic powerhouse was suddenly complicated by a set of novel – and potentially problematic – unknowns.

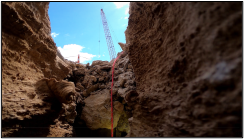

View upward from the cave shaft.

View upward from the cave shaft.

“Did we just discover a mega-cavern system – a new state landmark? Was there a rushing stream carving its way through the limestone? We didn’t know yet. And, more urgently, there was no suitable place to move the oxidation ditch if that was the case,” says Wes. “So, we started testing.”

The first move was to conduct Electromagnetic Conductivity Mapping and Multi-channel Analysis of Shear Waves seismic profiling. However, these tests didn’t provide conclusive data, so the team decided to drill several holes.

After survey, the drill rig takes a crack at the mystery.

After survey, the drill rig takes a crack at the mystery.

That’s when they got a break – literally. “The core barrel broke off in the rock and fell down somewhere we couldn’t see,” Wes recalls. “A $2,500 piece of equipment disappeared into the dark, but it was also a blessing in disguise because it let us know there was an anomaly. The barrel broke off because it hit empty space.”

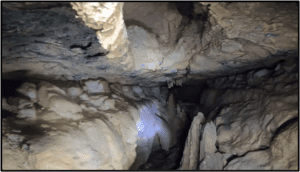

Empty space meant a larger cave was likely. Instead of more borings, the team got creative: they tied a GoPro to a paint roller and lowered it into the shaft. The video footage confirmed that the ledge led into a sizable cave.

The first cave footage taken by the GoPro.

The first cave footage taken by the GoPro.

The question now was the cave’s size and relationship to the oxidation ditch construction. Would a large, empty space bear the new weight?

“The problem became more urgent as construction was going up around us,” says Wes. “Obviously, we didn’t want to halt the work unless we had to, and we didn’t want to propose a new site for the oxidation ditch if we could verify the stability of the original site. We needed better information.”

Wes decided it was time for a new approach and brought in equipment typically used by the mining industry: a gyroscope laser scanner. Worth a few hundred thousand dollars, it looks like a six-foot-long torpedo with a camera, high-powered lights, and an oscillating laser capable of producing a 3-D model of underground features. These kinds of laser scanners usually explore undocumented mine shafts, so a mysterious cave was in its wheelhouse.

Insertion of the gyroscope laser scanner and its cave picture aided by powerful illumination.

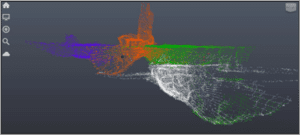

After four rounds of scanning from three different angles, the scanner gave the team what they were looking for: a model of the cave structure. The primary cave chamber was 27 feet tall, 34 feet long, and 4 feet wide, with a volume of about 780 cubic feet. Eons of rainfall flowing through the limestone created an underground space with the capacity of two concrete trucks.

The gyroscope laser scanner’s model of the cave.

The gyroscope laser scanner’s model of the cave.

At last, the team could start answering the major concerns. Filling the cave with grout or concrete wasn’t an option because it would divert rainwater to unknown locations. Drilled piers and micropiles were off the table because the required steel casing would corrode rapidly from moisture. After thorough analysis and discussion, the conclusion became clear: the cave’s unusual shape and position allowed the area to support the oxidation ditch. A reinforced concrete mat, combined with the cave’s unusual shape and thick roof of rock, would tolerate the new structure.

“We were happy to find that no remedial system or relocation was necessary,” says Wes. “It was a no-cost solution, and it didn’t slow the schedule.” The facility upgrade was completed, giving its capacity a crucial boost and supporting the economic expansion in the Jeffersonville area.

You can listen to SME’s Wes Hemp and Lochmueller Group’s Justin Ramirez discuss the River Ridge Commerce Center WWTP Expansion story on our podcast.